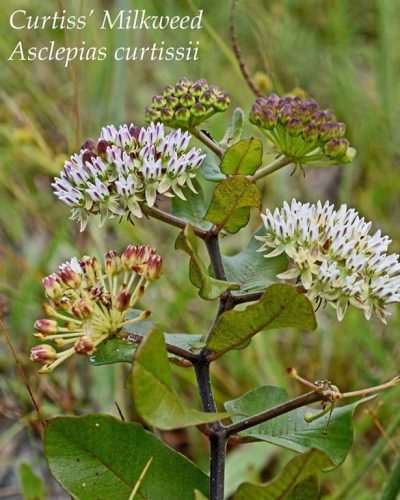

— Endangered Milkweed Found by IOF Director —

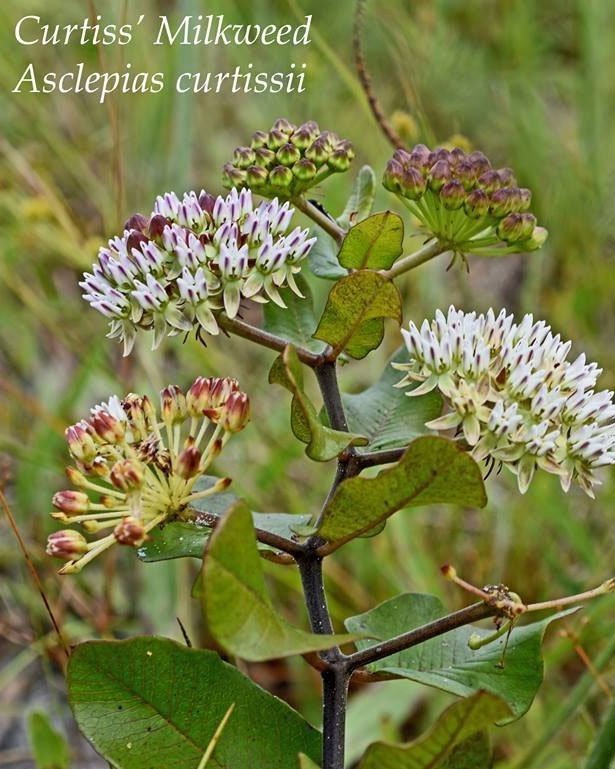

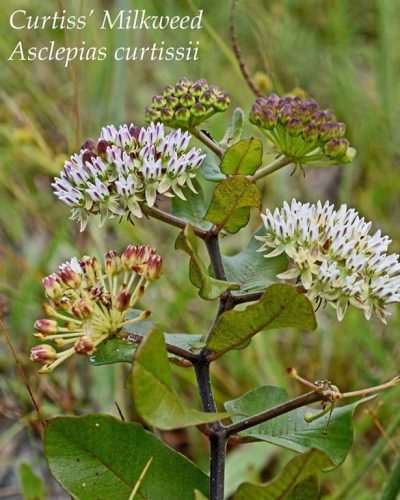

Species Profile: Curtiss’ Milkweed, Asclepias curtissii, is a Florida endemic species that is also an endangered species.

Imagine Our Florida Director, Andy Waldo, discovered this rare species while hiking. After confirming the plant was Curtiss’ Milkweed, Andy immediately notified the Park Rangers and a biologist who hiked back to the site with him and pinpointed the exact location of this endangered endemic species for further research.

What is an endemic species? It is a species that can only be found in a certain area. That means Florida is the only place you can find this species. As you can see by the range map, Curtiss’ Milkweed can be found in several counties across the peninsula of the state.

This milkweed is a herbaceous perennial species that can grow to heights of 2-4 feet tall. This species often dies back in the winter and may not re-sprout the following year. Curtiss’ Milkweed can lie dormant under the soil surface, re-sprouting after a year of dormancy. They stand erect when small. As they continue to grow, this milkweed will become somewhat vine-like, sprawling over large shrubs. There are no definitive studies on longevity, however, a Curtiss’ Milkweed living in a garden is at least 25 years old. This is definitely a long-lived species and as further studies are conducted, we will likely get a better picture of their longevity.

It should come as no surprise that such a unique and rare species would live in an equally unique and rare ecosystem. This plant can only be found in scrub and Flatwoods scrub habitats. These habitats are known for their very deep, sandy soil which is very low in nutrients and moisture. Within this unique habitat, the Curtiss’ Milkweed has an even more narrow micro-habitat. They are almost only found in sites that have disturbed soil. In modern times, that most often includes along the side of trails and dirt access roads in parks and wild spaces. More natural disturbed soil sites would include gopher tortoise aprons (the sand field in front of tortoise burrows), harvester ant sites, and other similar locations.

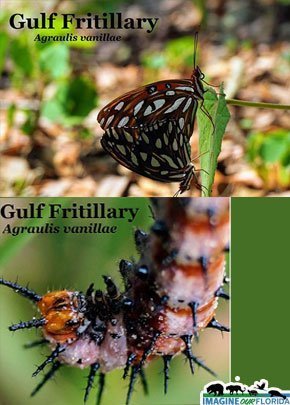

The Curtiss’ Milkweed has flowers that develop in clusters and last for about 5 days. They begin to bloom in June and can be found blooming into September. The flowers are pollinated by butterflies such as Ceraunus Blues, Hairstreak Butterflies, and several species of Skipper Butterflies. If the flowers are pollinated, the milkweed produces a fruit that takes 60 days to mature. Inside each fruit, there is an average of 68 seeds that, when the pod opens, are released and spread by wind.

Why is the Curtiss’ Milkweed so rare? Probably the biggest single reason is habitat loss. That very deep sand of the scrub community is also very desirable for construction. This species is also dependent upon fire to maintain an open forest floor and canopy. The policy of fire exclusion in the past further reduced the usable habitat of this species. Curtiss’ Milkweed is a very long-lived species but they have a low reproductive rate. This makes their recovery more difficult.

Their natural herbivores include the larva of the Queen Butterfly (Danaus gilippus) as well as deer. Curtiss’ Milkweed, like other milkweeds, has a thick, sticky, white sap that contains low levels of cardenolides which are toxic to vertebrates. The levels are low however and deer still will graze upon this species.

Given the status of this plant, as well as the difficulty to locate when not in bloom, park biologists came out to mark the location of the three Curtiss’ Milkweed found in this section of the park. A few more plants in another section of scrub which were located by a biologist who was studying scrub jays are awaiting identification. Documenting the location of these Curtiss’ Milkweeds will help park staff conserve this species within the boundaries of the park.

So the next time you are hiking, keep your eyes open for unusual flowers, plants, and wildlife. Like Andy’s, your discovery may lead to more research about a rare, endangered species.

*Range map used in this post came from the following link:

http://florida.plantatlas.usf.edu/Plant.aspx?id=1193

*Info for this post from The Pollination Biology and Ecology of Curtiss’ Milkweed (Asclepias curtissii) by Francis E. Putz and Maria Minno

*Images by Andy Waldo -Director Imagine Our Florida, Inc.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Recent Comments