Bok Tower Gardens is a serene must-see place that needs to be added to your must-visit list. There are amazing sights and loads of enlightenment in the gardens. Situated in Polk County, Florida, Bok Tower Gardens occupies a central location in Lake Wales, providing easy access to both Tampa and Orlando. For those using GPS navigation, the address 1151 Tower Blvd, Lake Wales, FL 33853 can be used. Bok Tower Gardens welcomes visitors every day of the year, including Christmas Day. You can buy general admission tickets either at the Entrance Gate or in advance through the online ticketing link provided. Note that special event and educational program tickets, with the exception of Brunch in the Gardens, include general admission for the day. The tickets provide access to certain Garden areas and the 3.5-mile Pine Ridge Preserve hiking trail.

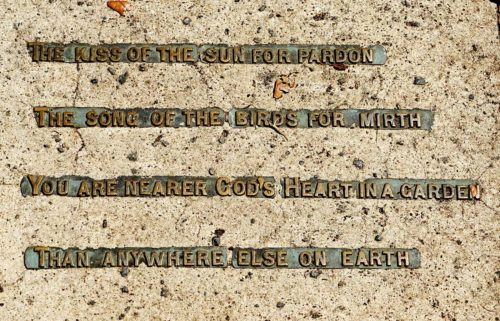

Bok Tower Gardens showcases one of the most remarkable works of renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. The sprawling historic landscape garden was designed to provide a serene and informal woodland setting with a series of romantic recesses, tranquil resting spots, picturesque vistas, and stunning views of the Singing Tower. The lush greenery, featuring acres of ferns, palms, oaks, and pines, serves as a vibrant backdrop for blooming foliage and seasonal bursts of azaleas, camellias, and magnolias, creating an ever-changing masterpiece, especially during the peak bloom season in spring.

The Gardens also boast a rich wildlife population, including 126 different bird species, as well as the endangered eastern indigo snake and threatened gopher tortoise. Bok Tower Gardens is designated as a site on the Great Florida Birding Trail, showcasing the natural habitats and diverse species of the region.

Visitors can explore the Gardens through paved primary pathways and several mulched secondary paths, some of which have inclines. There are two main pathways leading into the core Gardens, and visitors can choose from various routes to reach the Singing Tower, which is approximately an 8-minute walk from the Visitor Center.

Speaking of the Singing Tower, there’s another wonder of amazement located on the grounds which is a must-see. If you are wondering what makes the tower sing well let me let you in on a few tidbits. The music comes from a Carillon consisting of a set of at least 23 harmonically tuned bells made of bronze, a blend of copper and tin, and meticulously adjusted for pitch. The bells are stationary, and only the clappers move in a process called “hung dead.” This instrument operates purely mechanically, without any electronic components. The art of carillon originated in the 17th century in the low countries of Belgium and the Netherlands and remains prevalent in these regions to this day, with the highest density of carillons found there.

Fun Fact taken directly from the website: There are approximately 600 carillons around the world and only about 185 carillons in North America. Imagine if there were only 185 pianos on the whole continent – and we’re lucky enough to have one here!

That’s not all that’s housed in this gigantic tower. But I won’t spoil your visit by telling you every single detail. This work of art is truly a MUST SEE! MUST FEEL! MUST EXPERIENCE!

There are so many things to do at Bok Tower Gardens you can make it an all-day adventure! There’s even a hotel if you want to stay a while.

For more information click here: https://boktowergardens.org/

As always get outside and explore Our Florida!

Recent Comments