Florida Sandhill Crane

Common Long-Horned Bee

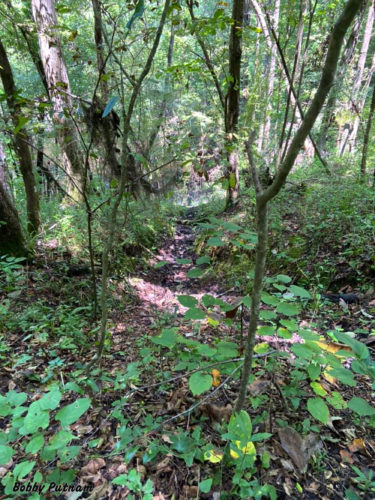

Devil’s Millhopper Geological State Park

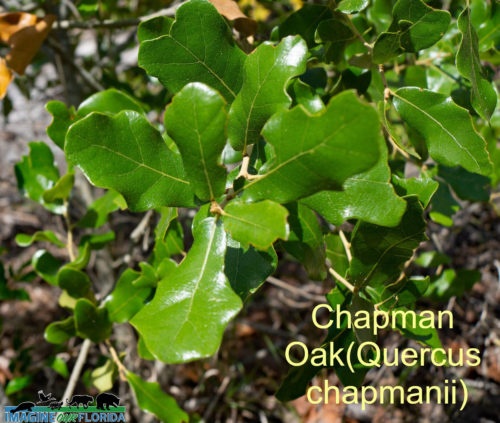

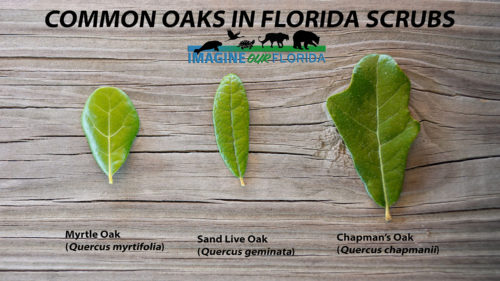

Scrubs

Scrubs are the remains of an archipelago that existed over 25 million years ago (Bostick, et al. 2005). Today, these ecosystems are characterized by low-quality sandy soil and are dominated by sand pines. The primary soil type is entisol which allows water to drain well and replenish the aquifer (The Nature Conservancy 1991). Plant species within the area are fire-adapted (Abrahamson, 1984).

Fire regiments are typically every 20 to 80 years and are facilitated by resin from sand pines, which are highly flammable (Menges and Kohfeldt, 1995). As a result, a fire rapidly spreads through the system and climbs to the treetops, creating what is referred to as “crown fires.” The heat from these fires facilitates a serotinous response, opening of sand pinecones. This heat is necessary for the release of seeds (Brendemuehl, 1990). Following fire regiments, a large and diverse collection of seeds are dispersed to the understory and can remain dormant for several years (Carrington ME, 1997).

Most sand pine scrub fires occur between February and June, with approximately 80% occurring during this time (Cooper, 1973). Historically, the primary means of fire ignition was lightning (Komarek, 1964.) Now, management practices include prescribed burns and mechanical harvesting of pines, which are recommended between March and May (Main and Menges, 1997).

Conservation efforts are necessary to maintain a healthy habitat for wildlife and to prevent extinctions, but there are other values that make conservation of these areas so important. Scrubs produce a relatively small economic value, but it is important that practices for harvesting sand pines are sustainable.

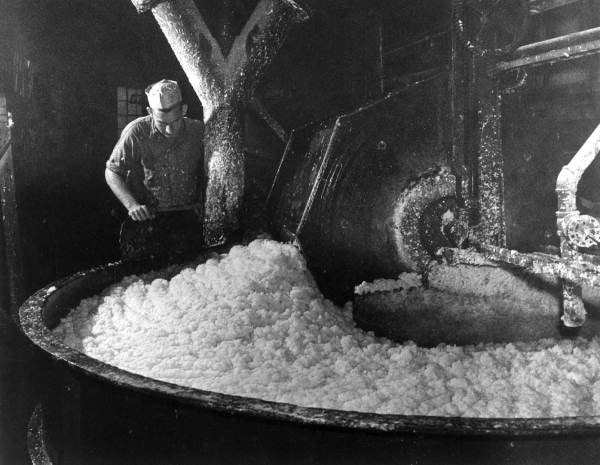

One sector that has been working on best management practices for sustainable use is the timber industry. An average of 40,000 acres a year of timber is produced from scrubs (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2012). Sand pines are mostly used for wood pulp. To produce sufficient pulp, the trees need to be at least 35 years old. Alternative growth rotations are necessary to ensure a sustainable harvest that has led to a cost-effective strategy of preparing the ground for seeding. This strategy includes clear-cutting, roller chopping, seeding, and 35 years of growth (Hinchee and Garcia, 2017).

Photo: Pine pulp at a paper mill in Pensacola 1947.

References:

Abrahamson W. 1984. Species responses to fire on the Florida lake wales ridge. American Journal of Botany 71.

Bostick, K. Johnson SA, and Main MB. 2005. Florida geological history. UF/IFAS Extension.

Brendemuehl R.H. 1990. Pinus clausa (Chapm. ex Engelm.) Vasey ex Sarg., Sand Pine. Silvics of North America 1:294-301.

Carrington ME. 1997. Soil seed bank structure and composition in Florida sand pine. American Midland Naturalist 137(1).

Cooper, R.W. 1973. Fire and sand pine. Sand pine symposium proceedings. General technical report SE-2. Southeastern Forest Experiment Station, USDA Forest Service; Marianna, Florida. 207

Hinchee J and Garcia JO. 2017. Sand Pine and Florida Scrub-Jays—An Example of Integrated Adaptive Management in a Rare Ecosystem. Journal of Forestry 115:230-237

Komarek EV Sr. 1964. The natural history of lightning. Proceedings of the Tall Timbers fire ecology conference 8. Tall Timbers Research Station; Tallahassee, Florida.

The Nature Conservancy, Archbold Biological Station, Florida Natural Areas Inventory. 1991. Lake Wales/Highlands Ridge Ecosystem CARL Project Proposal, January 1991.

Lower Wekiva River Preserve State Park

Saltwort

Cedar Key

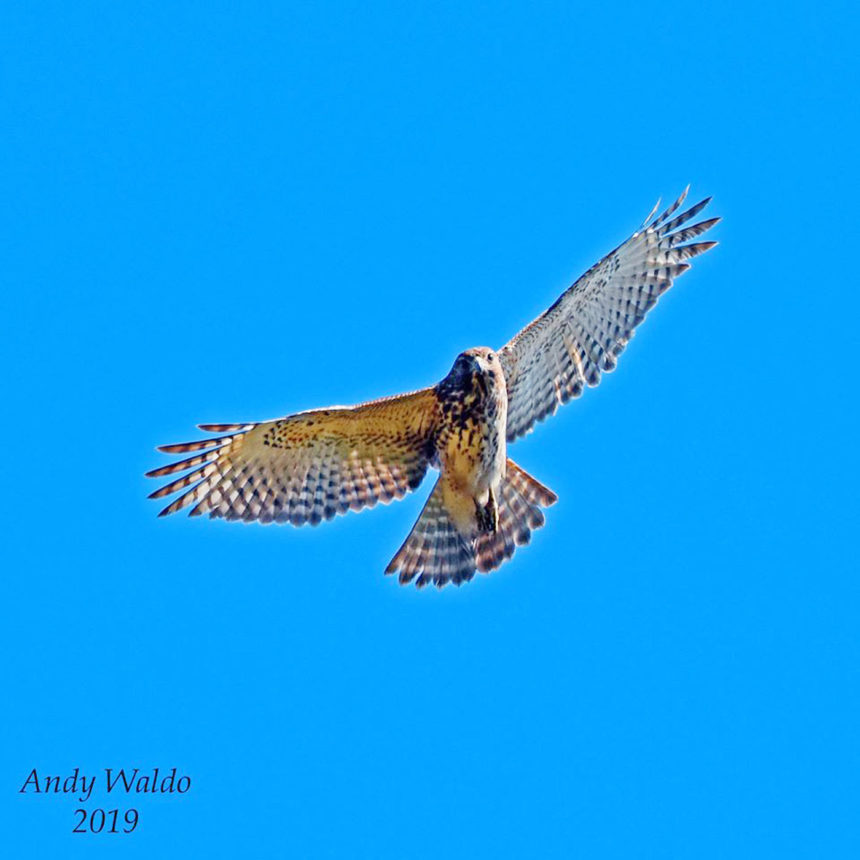

If you are looking for a place to escape the hustle and bustle of life, look no further than Cedar Key. A place where the locals greet you with friendly smiles, where shorebirds frolic in the waters, ospreys soar overhead, and a multitude of habitats are waiting to be explored. Your trip begins on Highway 24 in Levy County, where you drive from the mainland on low bridges, over picturesque channels, and salt marshes onto Cedar Key.

A pencil factory was once located on Cedar Key, where the cedar trees supplied the wood for the pencils. The first Florida coast-to-coast railroad ended at Cedar Key before it was rerouted to Tampa. Shell mounds give us a look into the lives of the indigenous people who called Cedar Key home long ago. Today, about 800 permanent residents welcome visitors to their unique island.

Cedar Key is a Nature Lover’s paradise, where visitors can stroll along nature trails, birdwatch, and paddle in the Gulf. The federally protected sanctuaries lure both shorebirds and migratory birds. Go on a coastal guided tour. Kayaks, paddleboards, and motorboats are available for rent to explore the Gulf of Mexico. Campgrounds provide space for your RV or tent.

Saunter along the Cedar Key Railroad Trestle Nature Trail, a 1,700 ft path of old Fernandina Cedar Key rail line. Let the cedars and pines shade you as the songbirds serenade you with sweet melodies. Watch for a beautiful variety of wildflowers with butterflies flitting about. At Cemetary Point Park, there is an easy walk along a 1299 foot boardwalk through mangroves. Cedar Key Museum State Park Nature Trail is a short stroll where you will see gray squirrels playing, woodpeckers in search of food, mocking birds tweeting, and green tree frogs resting.

The swamps, marshes, and wetlands are home to American avocets, ibises, roseate spoonbills, herons, egrets, pelicans, and more. Dolphins play in the Gulf. Thousand of birds visit during the fall and winter migration including, rare white pelicans. With its laid-back Old Florida vibe, Cedar Key is a perfect addition to your list of places to visit.

Photo Credit: Dan Kon

Key Deer

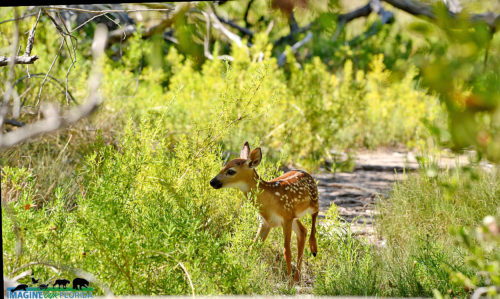

Key Deer (Odocoileus virginianus clavium) are members of the North American White-tailed Deer family. They are the smallest species and are endangered.

Found only in the Florida Keys, these beautiful animals were poached and suffered from habitat loss, leaving only a few dozen left in the wild. In 1967, Key Deer were listed as endangered. The protections afforded them under the listing, as well as the establishment of the Key Deer refuge, have brought their population up to nearly 1,000. Big Pine Key and No Name Key are home to 3/4 of the population.

Key Deer dine on over 150 species of native plants. Adult females weigh about 65 pounds, and adult males weigh about 85 pounds. During the rut, the males lock horns as they compete. Breeding takes place in the fall. Between late spring and early summer, does give birth to one white-spotted fawn. When startled, Key Deer will raise their tails, exposing their white fur.

Humans can be a threat to Key Deer. When visiting The Keys, drive slowly, especially at night and in the early morning. Keep them wild. Resist feeding Key Deer unhealthy human food.

Photo Credit: Aymee Laurain and Dan Kon

Recent Comments