“This park is like nothing else in Florida. Being able to see the stars at night in unbelievable detail was absolutely worth the trip.” Jonathan Holmes, IOF Contributor

There is a place in Florida that is world-renowned for stargazing. Designated as a Dark Sky Park due to the absence of light pollution, the stars and planets can be enjoyed the way nature intended.

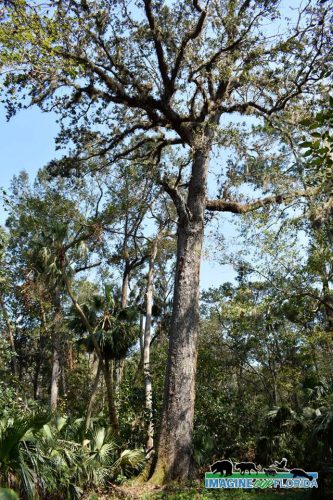

Located in Okeechobee, Kissimmee Prairie Preserve State Park is part of the headwaters to the Everglades and is the largest remaining dry prairie ecosystem in Florida. Once spanning coast to coast and from Lake Okeechobee to Kissimmee, the prairie has been reduced to a mere 10% of its original expanse.

Throughout the years, humans have altered the prairie to suit their needs. The State Park is working to restore the land to pre-European influence. Over 70 miles of ditches and canals have been restored to swales and sloughs. Old plow lines are slated for reconditioning, and a cattle pasture will be restored to native shrubs and grasses. As a fire and flood dependent ecosystem, these efforts will allow the prairie to thrive once again.

The most famous resident of the prairie is the Florida Grasshopper Sparrow. Critically endangered, the sparrows rely on a healthy prairie ecosystem for survival. Crested Caracaras, Burrowing Owls, Wood Storks, Swallow-Tail Kites, and White-Tail Kites find refuge at the park. Watch for Bald Eagles, White-tailed Deer, and Indigo Snakes. Native wildflowers are abundant. Look for Blazing Stars, Yellow Bachelors Buttons, Meadow Beauty, Pipewort, and Alligator Lilies.

There is plenty to do at Kissimmee Prairie Preserve. Hiking, horseback riding, and biking are wonderful ways to experience Nature up close. Camping, primitive camping, and equestrian camping are offered for those who want to spend the night. A ranger-led prairie buggy tour and an astronomy pad are spectacular ways to enjoy the park.

For reservations, times, fees, and more click here:

https://www.floridastateparks.org/…/kissimmee-prairie-prese…

Photo Credit – Jonathan Holmes

Recent Comments